publications

2022

Davidson P (2022), Is this the end of the Job Network model? The evolution and future of performance-based contracting of employment services in Australia. Aust Jnl Social Issues, Vol 57 No 3 pp 476-496.

[winner of Peter Saunders Prize for best article in 2022]

presentations

2024

Four pillars of Australian workers’ minimum incomes, Centre for Future Work Carmichael Centre symposium, Melbourne, 17 October 2024

2018

Contracting employment services to outcomes: is this the promised land?

Presentation at Melbourne Institute Public Economics Forum

Canberra, Tuesday 6 September 2016

Peter Davidson

Learning to swim at the deep end

Presentation to Jobs Australia conference, Hobart, November 2017, Peter Davidson

The end of Work for the Dole?

Work for the Dole was the flagship employment program of the Abbott Government (Abbott reprised his role as the program’s founder as a Minister in the Howard Government). From July 2015, working for benefits for at least 15 hours a week became the ‘default activity’ for 6 months of every year for unemployed people. One fifth of employment services spending is devoted to the program – almost $300 million a year. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in remote communities face continuous Work for the Dole for 25 hours a week.

The Turnbull Government seems less enthusiastic: it has cut the program back: instead of Work for the Dole after 6 month’s unemployment, from April 2017 unemployed young people will be enrolled in the ‘Youth Jobs Path’ program which combines work-readiness training with private sector internships.

Work for the Dole has always been controversial, but does it work? This blog looks at recent evidence of the impact of ‘work for benefits’ schemes on transitions to paid employment in the UK and a 2014 evaluation of Work for the Dole in Australia.

The birth, decline and re-birth of Work for the Dole

Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s first Ministerial gig in the Howard Coalition Government was in employment services. One of his first programs was ‘Work for the Dole’. Abbott made it clear that one purpose of the program was to increase incentives for people to leave benefits.

‘If they’re not working for wages they’ll be working for the Dole’ (Tony Abbott, Minister for Employment Services)

Work for the Dole – in which long term unemployed people were compelled to work for their benefits for community organisations for 15 hours a week for 6 months – was the Howard Government’s flagship employment program. By the mid 2000s, it was the default compulsory activity for long term unemployed people for 6 months of every year. ‘Job avoiders’ had to work for their benefits for 25 hours a week for 11 months a year.

The Rudd Labor Government kept Work for the Dole as one of a series of compulsory program options organised by Job Services Australia (JSA) providers for long term unemployed people, but it was no longer the ‘preferred’ option. This meant it was no longer the ‘default’ activity for people who failed to choose another program, and was no longer separately funded (instead JSA providers had budgets to draw upon to finance a range of options). Providers mainly chose to refer long term unemployed people to vocational training programs instead and participation in Work for the Dole plummeted.

Now it’s back with a vengeance! The program was expanded across the country from July 2015. People on Newstart Allowance for 12 months must undertake 15 hours a week’s unpaid work for 6 months, unless they’ve already enrolled in an alternative employment or training program approved by their ‘Jobactive’ (the new JSA) provider. People under 30 years will work unpaid for 25 hours a week after 6 months’ unemployment.

In remote Indigenous communities, people on unemployment payments face 11 months a year of working for the dole for 25 hours a week – the same as the ‘job avoiders’ of yore. Unlike the previous Community Development Employment Program in which they worked in community-controlled services and received ‘top up’ payments (so that it was more like waged employment), the new ‘Community Development Program’ (CDP) offer unpaid work and other unspecified ‘activities’ that are mainly coordinated by for-profit employment services companies. The upshot has been a steep rise in financial penalties for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for breaching their 25 hour a week requirement.

Controversy

From its beginning in 1997 Work for the Dole attracted controversy.

Some argued that unemployed workers were being exploited in work for which they were paid less than the hourly minimum wage. Former Opposition leader Kim Beazley called the program a “chain gang”.

In anticipation of these claims, the original scheme was limited to 15 hours a week – roughly equivalent to an hourly ‘training wage’. Later, a $10 a week allowance was paid for travelling expenses. In 2006, a ‘full time’ variant of Work for the Dole requiring 25 hour’s work each week (about $10 per hour in current values) was introduced as a punishment for people identified by Job Network providers as ‘job avoiders’. Interestingly, it was rarely used because providers preferred to keep unemployed people under their own close supervision while they searched for jobs.

Others criticised the nature of the work on offer (usually ‘make work’ activity in low-productivity jobs) and the lack of training. Supporters argued the program improved work motivation and ‘soft skills’ like punctuality and communication and improved self esteem. However, in an early official evaluation of its impact on self esteem. Dr Winefield found that it had no impact and that participants were already strongly motivated to work:

“Although, WFD had no impact on participants’ self-esteem, it had clear ongoing benefits on other measures of psychological well-being, although whether these benefits were lasting or short-lived remains to be seen. Research has shown that self-esteem is sensitive to changes in employment status. The current finding implies that participants did not perceive WFD as a change in their employment status. Similarly, although WDF had no impact on work involvement, the level of work involvement was so high that there was little room for improvement.” (Winefield, A 1999, “Measuring the impact of the Work for the Dole pilot projects on work ethic and self esteem.”)

The views of participants varied: many objected to being forced to undertake work they felt wasn’t helping them find paid work while others enjoyed the work or companionship with fellow unemployed workers.

Crucially, Work for the Dole is not a labour market program. It does not have an explicit goal of helping people secure paid employment. Its official goals are mixed. They range from fulfilling a ‘moral’ requirement that unemployed people should ‘give something back’ for their benefits, to discouraging people from staying on benefits, to building soft skills and raising self esteem, and undertaking work of benefit to local communities. Depending on the audience and political mood, it has been portrayed either as punishment for ‘bludgers’ or a balm for the psychological harms of prolonged unemployment.

The program’s chameleon-like character makes it hard to evaluate objectively. To my way of thinking, the litmus test for any employment program is whether it improves people’s job prospects. If not, then there’s no good reason to force people to undertake it. Whether this is the case has been debated among experts from the outset.

Evaluating employment programs

The best way to assess this is a ‘net impact evaluation’, in which employment and ‘off-benefit’ outcomes are compared over time with outcomes achieved by a similar ‘control group’ of unemployed people not referred to Work for the Dole. Employment programs have three different effects:

- Referral or ‘threat’ effects: Some people leave benefits rather than participate in the program

- Attachment or ‘lock-in’ effects: Participation in some programs reduces job search activity

- Program effects: Ideally, participation in a program improves employment prospects, for example by improving skills, putting people in contact with employers who might take them on, or by improving the efficiency of job search.

The overall impact of an employment program equals the referral effect + the program effect – attachment effects. Quantitative studies should be supplemented by qualitative research that examines what actually happens to unemployed people and prospective employers when they participate in a program. Here I focus on net impact studies of work for benefits programs.

Previous studies of employment impacts

Economist Jeff Borland conducted the first and only independent net impact study of Work for the Dole. He found that participation in the original pilot scheme for young unemployed people in the late 1990s actually reduced the probability that unemployed people had left income support 12 months after referral to the program. He suggested this was due to attachment effects (they were too busy with Work for the Dole to search for jobs effectively). There appeared to be no significant program effects.

Subsequent official net impact studies by the Employment Department found reductions in reliance on unemployment payments after referral to Work for the Dole. A study in the mid 2000s found that referral to the program reduced reliance on income support 12 months later by 6.1 percentage points. (Dept of Education Employment and Workplace Relations 2010, ‘Labour market assistance, a net impact study.’)

That’s not a bad outcome for a labour market program but I’d be more confident of the results if they were backed by independent studies. International studies of the effects of work for benefits schemes give little cause for optimism. An early literature review by MDRC Research, a prominent independent employment program evaluator in the US, found that work for benefits schemes did not improve people’s job prospects. A later report by the New Zealand Department of Labour concluded that neither New Zealand’s ‘community program’ nor similar programs in other countries improved job prospects.

Evaluating Work for benefits schemes in the UK

The most thorough recent evaluations of work for benefit schemes were undertaken in the UK: a country with a rare record of careful independent evaluation of its labour market programs. Here we examine recent evaluations of two UK work for benefit programs: the Mandatory Work Activity (MWA) program introduced in 2011 and the Community Activity Program (CAP) introduced in 2013.

Mandatory Work Activity

Mandatory Work Activity comprised 4 weeks of compulsory work for benefits for 30 hours a week. It was targeted towards people at risk of long term unemployment. It attracted much controversy and a successful British High Court challenge by an unemployed woman required to work for her benefit for a private employer.

The official evaluation of MWA found significant referral or ‘threat’ effects on the likelihood of benefit receipt:

“in the first 3 months MWA decreased the likelihood of claiming benefit by up to 5 percentage points: the proportion of referrals in receipt of benefit was 77% at week 10 compared to 82% for non-referrals at week 10. This strongly suggests that MWA had caused a deterrent effect of claiming benefit – a very high proportion (64%) of those who did not start signed off their JSA claim.

But, as shown in the graph below, these effects were reversed within another three months, as many of those who left benefits returned:

“However, in the subsequent period the impact decreased, returning to zero by 21 weeks following the referral (benefit receipt for both referrals and nonreferrals was 74%). This means that in this period a higher proportion of individuals returned to benefit amongst referrals than non-referrals. Overall, the benefit impact during the first 21 weeks equated to referrals being off benefit for an average of about 4 days more than had they not been referred.” p39.

Effects of Mandatory Work Activity on benefit reliance

Note: green line represents MWA participants

Note: green line represents MWA participants

Crucially, the program had no impact on people’s employment prospects (so those who left benefits weren’t for the most part getting jobs and some were diverted to disability pensions). This is shown in the graph below:

“unlike for benefit, a MWA referral had no impact on the likelihood of being employed compared to non-referrals. This suggests that although the benefit impacts suggested a deterrent effect from claiming benefit for the first 10 weeks, individuals were not going into employment.” p40

Note: green line represents MWA participants

These data suggest that this short work for benefits program had significant ‘threat’ effects that were later reversed, but no impact on the future job prospects of unemployed people. What did the Government do when it received this evaluation? It expanded the program! As labour market researcher Jonathan Portes pointed out in a blog:

“Briefly, what the analysis shows is that the programme as currently structured is not working. It has no impact on employment; it leads to a small and transitory reduction in benefit receipt; and worst of all, it may even lead to those on the programme moving from Jobseekers’ Allowance to Employment and Support Allowance. Sadly, the DWP’s press release doesn’t mention any of these key points. Nevertheless, one would naturally assume that as a consequence the programme would be redesigned to achieve better outcomes.

However, in a Written Statement, the Minister for Employment said: ‘I am also pleased to announce the Government has decided to expand the Mandatory Work Activity scheme. The expansion will enable Jobcentre Plus to make between 60,000 and 70,000 referrals to Mandatory Work Activity each year, based on the current experience of the scheme, at a cost of an additional £5 million per annum. This decision has been taken as the result of careful consideration of the positive impacts demonstrated within the Impact Assessment.’ Unfortunately (says Portes) it is very difficult indeed to reconcile this statement with the impact assessment itself.”

Community Action Program

In 2013 a new work for benefits program called Community Action Program (CAP) was trialled for very long term unemployed people (2 years out of work). This was carefully evaluated as part of a ‘very long term unemployed trailblazer’ scheme.

The scheme had these features:

“A randomised controlled trial to give a high degree of confidence that any observed differences in outcomes are attributable to the support options,

- A 13 week pre treatment period to test deterrence, informing and maintaining awareness of forthcoming support throughout the period, and

- A 26 week period of treatment consisting of either:

– Standard Jobcentre Plus support – this is the control group within the trailblazer and consists of flexible and personalised adviser based support.

- Community Action Programme (CAP) – delivered by contracted providers and comprising 26 weeks of full time work experience or provider-led job search support.

- Ongoing Case Management (OCM) – an intensive offer of flexible and personalised adviser based support, delivered by Jobcentre Plus (JCP) through increased interventions over 26 weeks.” p6

A randomised trial is the ‘gold standard’ of net impact studies. Unemployed people were randomly assigned to a treatment group referred to the CAP, an alternative scheme called ‘ongoing case management’ (an intensive form of job search assistance), or a control group who received ‘standard JobCentre Plus support’ (mainly job search assistance) as shown in this flow chart:

The likelihood that unemployed people involved in the trial were still receiving income support up to 91 weeks after referral to each of these three options was compared. The results are shown in the graph below: 68% of benefit recipients in ‘standard JobCentre Plus support’ still received benefits 91 weeks later, compared with 66% of those referred to CAP and 64% referred to ‘case management’. So referral to CAP reduced benefit reliance by 2%, which was 2% less than the impact of case management.

Effects of CAP, Case Management and standard job search assistance on benefit reliance The graph below compares employment outcomes for those referred to CAP and the other two options in the trailblazer. It turns out that CAP had no significantly greater impact on employment than the standard ‘Jobcentre Plus’ option. Ongoing case management did increase the likelihood of employment compared with the standard service, by just 1%.

The graph below compares employment outcomes for those referred to CAP and the other two options in the trailblazer. It turns out that CAP had no significantly greater impact on employment than the standard ‘Jobcentre Plus’ option. Ongoing case management did increase the likelihood of employment compared with the standard service, by just 1%.

So the recent British evaluations confirm what others have found: referral to work-for-benefits programs increases the likelihood that people will leave benefits, but many soon return. Participation these programs has no significant impact on the likelihood of paid employment. A fair summary of the pros and cons of these programs was offered by Tony Wilson from CESI, the British employment services advocacy body. His conclusion: it’s reasonable for unemployed people to be required to join programs that help them secure a job and Governments should fund them, but work for benefit schemes generally aren’t worth the effort.

Evaluation of the 2014 Work for the Dole scheme

When the Abbott Government restored direct funding for Work for the Dole and also its previous ‘default program’ status in 2014, it authorised an evaluation of the impact of the new scheme in a number of ‘trial’ areas.

This found that in those areas, the new scheme increased participation in Work for the Dole by 28 percentage points for unemployed people with similar characteristics. So it was successful in reviving the program. However, 27% of participants did not complete the program and 60% of unemployed people responding to a survey agreed that the program’s aim was to ‘put people off claiming benefits’. Consistent with this, the report found that:

‘There is clearly stigma associated with the programme and those who participate in it.’

The new program was less successful in helping people secure jobs.

While the report estimated that the program:

increased the rate of part-time/casual paid employment reported to JSA providers by 7 percentage points more than in the comparison areas controlling for other characteristics (from a baseline of 13%).

it warned that this was due to an unknown extent to people declaring existing employment on referral (i.e. a ‘threat effect’).

The report estimated the impact of the program on placement in new jobs as follows:

‘an additional 2 percentage point increase in the probability of job seekers having a job placement controlling for other characteristics (from a low baseline of 14%).’

It’s not clear from the report exactly how the net employment impact of the 2014 scheme was measured: the report refers to a ‘difference in differences’ method using administrative data, but warns that it was too early in the program’s development to properly measure its employment impact. Unlike the British evaluations, there was a lack of longer-term data to assess how many people returned to benefits after leaving them (The report refers to ‘short term’ employment impacts but it’s not clear how soon after referral to the program these were measured).

A key finding of the 2014 evaluation on the employment impact of Work for the Dole appears to be that participation in the scheme increased the probability of future employment by 2 percentage points (interestingly, the same as the British CAP program), which may well be within the net impact study’s margin of error. The evaluation suggests that ‘threat effects’ (such as declaration of existing employment) are significant but does not appear to measure them directly. Yet, similar ‘threat effects’ would probably be achieved by any program of compulsory, intensive ‘activation’ of unemployed people.

Participation in an employment program should make a difference to people’s job prospects and work-for-benefits schemes do not do this. To refer people to a scheme that has no impact merely to discourage them from staying on benefits is a cynical exercise.

Conclusion

To summarise: six months of compulsory work-for-benefits has none or very marginal impact on the future job prospects of long term unemployed people and the $300 million spent on the scheme would be better invested in other programs. Even the standard job search assistance offered by Jobactive providers (limited as this is for most people) probably yields better employment outcomes.

The Australian and British Governments are among the biggest investors in work for benefits schemes. Despite public commitments to ‘evidence based policy’ and ‘value for money’, these Governments are slow learners.

Activation policies in the 1990s and 2000s: Denmark and the United Kingdom compared.

I haven’t blogged for a while. My excuse is that I’m writing up my PhD thesis comparing the emergence of activation policies in four countries: Australia, United Kingdom, Denmark, and the Netherlands. As you can imagine, this is taking a while!

In case this is a topic that interests you, here’s a sample of my work: a paper I presented at the FISS conference in Sigtuna Sweden in 2014 comparing activation in the UK and Denmark:

The conclusion? These two pioneers of activation policy took the same ideas – structural unemployment, activation, and New Public Management, and implemented them differently. They put the activation policy jigsaw together in different ways. Path dependency was at work here: the two countries had very different sets of labour market and social security institutions, and still do.

The ‘Qualification Program’: Norway’s answer to entrenched long term unemployment?

With an unemployment rate of 4.1%, Norway must be getting a few things right. In 2007 they did what few countries do: seriously invest in an employment program to reduce entrenched, long term unemployment. The two-year ‘Qualification Program’ aims to overcome social barriers to work as well as low skills. Participants must undertake full time activities and caseloads are 1:18. In a new twist on work incentives, they receive higher income support than similar unemployed people. It’s not cheap, but 4 years after starting the program, long term unemployed people are 18% more likely to be employed.

Seven years after the global recession, long-term unemployment is worrying experts and policy makers across the world, even in the US where time-limited benefits and a ready supply of low skilled low paid jobs previously seemed to hold it at bay. Yet few countries are getting to grips with the core of the problem: by investing in programs that bring the most disadvantaged long term unemployed people into jobs. One exception is Norway, which with an unemployment rate of 4.1% can boast success in labour market policy.

In 2007, Norway introduced its ‘Qualification Program’ (or ‘QP’) for people at risk of prolonged unemployment, including those who lack unemployment insurance entitlements and rely on municipal social assistance payments: a group often neglected European labour market programs. The name is a bit misleading: its aim is to ‘qualify’ people for jobs by overcoming social barriers to work as much as weak vocational skills.The program combines secure and generous income support (higher than most social assistance payments) intensive employment and social support over a two year period, and a requirement to engage full time in those activities.

It is being evaluated with an emphasis on its long term impacts. One evaluation found that it boosted the probability of employment for a group of unemployed people whose prospects were otherwise weak by an average of 10% after 2 years and 18% after 4 years. This comes at a price: the average annual cost of additional employment assistance through the program is EUR$6,000 spread over 2-3 years. The higher unemployment benefits cost a similar amount. Much or this is eventually retrieved as more program participants move off benefits: a key evaluation question is how much.

Context

Norway has two systems of unemployment payment: unemployment insurance paid by industry based social insurance funds which requires a contribution history, and social assistance which is run by municipalities. Unemployment insurance is relatively generous but social assistance payments are generally lower and are not legislated. Municipalities have discretion in setting rates of payments and other conditions of payment.

In 2007 when the QP was introduced the Norwegians faced a common problem in European unemployment benefit systems: employment assistance was fragmented and there was poor cooperation between the public employment services and municipalities to assist people on social assistance payments to secure work. A common assumption was that social assistance clients were not ’employable’.

One part of the solution was a merger of the benefits agency and public employment service, and formal collaboration arrangements between this new agency and municipal welfare offices to meet the employment needs of both insured and uninsured unemployed people. Offices of the new ‘NAV ‘agency continue to serve insured unemployed people but are co-located with municipal social services to make labour market assistance more accessible to people on social assistance payments.

The other part was the QP which has been rolled out region-by-region in conjunction with the establishment of NAV offices. This facilitates evaluation since similar people are assisted through the ‘old’ and ‘new’ systems in different localities.

Target group

The Programme is targeted at people:

- with ‘significantly reduced earning ability’ and no or limited national insurance rights;

- who are ‘trapped’, or in danger of getting trapped, in a passive situation characterised by income poverty; and

- who are considered to have a chance of getting a job through individual follow-up, even if this implies a lengthy process.

This assessment is conducted by the NAV, which administers the program. As the above criteria suggest, there is much room for discretion when making referrals. Assessors do not use a statistical assessment tool such as the Australian Job Seeker Classification Instrument. Most participants previously received municipal social assistance but unemployment insurance recipients may also meet the criteria.

Participation is voluntary but once enrolled, participation in employment related activities is a condition of receipt of the ‘Qualification Benefit’ (discussed below).

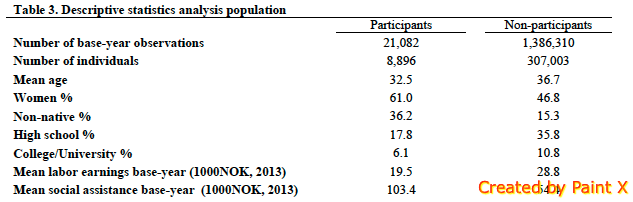

The table below compares unemployed people referred to the QP and those not referred. QP participants are much more likely to be women, migrants, and to lack complete high school qualifications. They are much less likely to have labour earnings over the previous year. This all suggests that QP participants are significantly more disadvantaged than the average unemployed person.

Income support

One innovative feature of the QP is that participants receive higher income support payments (in most cases) than they would if on social assistance. This is based on the view that people who are severely disadvantaged in the labour market need stability in their incomes and lives in order to fully benefit from employment assistance. This is a departure from the conventional view (informed by neo-classical economics and research on transitions to employment among less disadvantaged unemployed people) that lower benefits and time limits spur people to search for jobs more intensively.

I suspect it’s also an attempt to patch a few holes in the social assistance system, which (unlike most countries) is not based on uniform legislated entitlements. Instead each municipality determines rates of payment and this has led to inequity and inconsistency.

A second innovation is that the payment is not income tested. If an unemployed person secures full time work within the two year period of the program they keep the full benefit as a wage supplement.

The qualification benefit for a single adult is NOK145,762 (approx. EUR17,000) per year for participants 25 years or older, while those below 25 years receive 2/3 of this.

By contrast, unemployment insurance for a single person is 62% of the previous wage and the average wage is around EUR50,000 (so an former average wage-earner might receive EUR30,000) which can be claimed for up to two years. Those ineligible for unemployment insurance may transfer to the much lower social assistance payments.

So the ‘qualification benefit’ is high by OECD standards and higher than what social assistance clients would otherwise receive, but lower than unemployment insurance.

Employment assistance

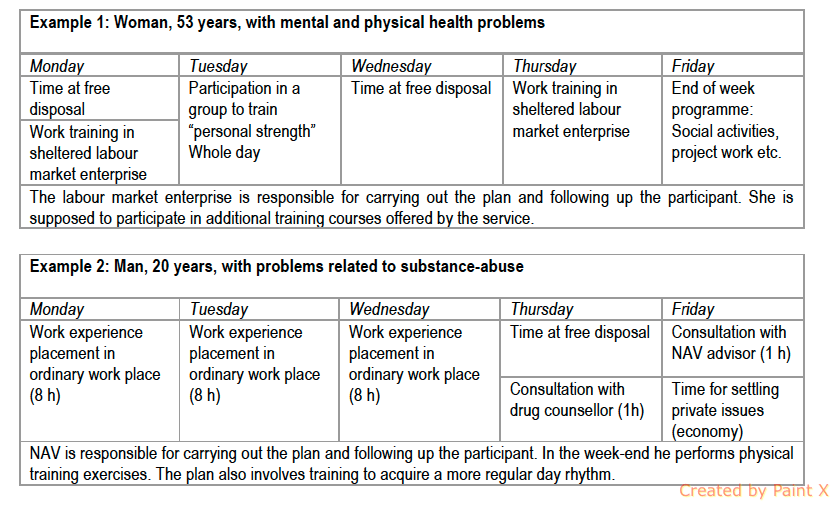

In return for the Qualification Benefit, participants must engage in 37 hours a week of work preparation activity negotiated with the NAV. Examples of these activities are provided below.

As these examples show, a wide variety of activities are included on a spectrum from immediate referral to an employer or work experience placement to therapeutic programs and sheltered employment for those assessed as most disadvantaged.

Participation in the activities is compulsory, and continues until the individual secures paid employment (in which case they continue to receive the benefit) or abandons the benefit.

A key feature of the program is the low caseloads. Each case worker has only 18 clients at a time.

Impact

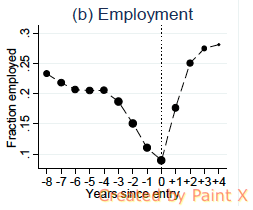

A quantitative evaluation of the impact of the program on employment found that the probability of being employed fell by an average of 9% in the first year (due to the ‘lock in effect’ of program activities), then rose by 10% after 2 years and 18% after 4 years. The graph shows the average proportion of each year spent in employment before and after entry to the program. The decline in employment in the years leading up to program entry was attributed to the labour market disadvantage of participants, and the improvement was attributed to the program.

These are strong results for a program targeting disadvantaged, long term unemployed people. There are a few qualifications: most of the jobs obtained were part time and low paid, and after four years, the average cost of the program was still not recouped through lower benefit payments. The latter result is due in part to the design features of the qualification benefit: for the two years of the program the benefit is paid regardless of labour earnings at a level higher than most social assistance payments.

How well does it work and could it work better?

Few programs are effective in assisting the most disadvantaged long term unemployed people into jobs, on a large scale. Activity requirements and job search assistance alone are not often effective for that client group. They need more intensive (therefore costly) programs to build work capacity, link them with a suitable employer (not just the first job available), and ensure that it lasts.

‘Lock in effects’ from intensive work experience training, or therapeutic programs are common because they delay job search. What matters here is the strength and sustainability of the subsequent ‘treatment effect’. If the QP does boost average employment impacts by 18% after four years, the delayed impact is probably worth it. A 10 percentage point improvement in job prospects after two years is also pretty good, especially if their chances were very low to begin with.

If these employment outcomes were full time, sustained jobs it’s very likely the program would eventually pay for itself, since most participants were otherwise likely to remain on income support (and not pay income tax) for years to come. However, the evaluation finds that the program is not yet ‘cost neutral’ four years after program entry (on average). The extra costs (the higher qualification benefit, more intensive employment assistance, and loss of potential earnings in the first two years) still exceed the gains at that stage though the gap is closing. The evaluation suggests that the employment gains after four years would have to be sustained for longer before the financial benefits of the program to overtake its costs.

The evaluation may have exaggerated the costs to government. To assess this accurately it would have to subtract the unemployment payments clients would have received on average over the four years in the absence of the program. Also, no account is taken of the effects of the program on income tax receipts.

There are three uncertainties about the estimated impacts of the program.

First, did the evaluation effectively control for ‘unobserved characteristics’ and the possibility of selection bias into the program? While it targeted disadvantaged job-seekers, voluntary programs usually involve an element of ‘creaming’ since the more motivated and confident you are, the more likely you are to join. The risk of ‘creaming’ is heightened by the discretionary nature of assessment of eligibility for the program.

Second, to what extent are the strong long-term results due to the the fact that the program is new and run on a (relatively) modest scale? It’s common for a new program assisting a group who previously received little or not help (and were not expected to actively search for jobs) to have good outcomes. Will its effectiveness decline once it’s brought up to scale?

The third question is the most interesting: to what extent can the results be attributed to the qualification benefit or the more intensive employment services? Financial incentives to take up employment (such as the lack of an income test) often don’t work well for disadvantaged job-seekers because their main problem is not a lack of incentive to take up job offers: it’s that they receive too few of them.

The main advantage of the higher and more stable qualification benefit is likely to more subtle: that it supports and rewards people who commit themselves to the program. An interesting feature of the benefit is that it is paid like a wage (by a payroll office) rather than a social assistance benefit.

I suspect it is the more intensive employment services (and the requirement to stick with them to keep the benefit) that make the most difference. A caseload of 18 people is well below the 100 or more in most employment service systems (including Australia’s). If the case workers are well trained and focus on employment outcomes, that alone should make a big difference.

Here there appears to be a weakness in the implementation of the program: most of the caseworkers apparently come from a municipal social service background. Their focus seems to be mainly therapeutic (removing barriers such as homelessness or addictions before turning to employment goals). In other countries where social assistance recipients were first ‘activated’ into the labour market, including Denmark and the Netherlands, considerable effort was devoted to retraining and re-orienting caseworkers from social work to employment assistance.

The nature of the employment assistance received is also critical. In the examples above, the client referred to work experience in a regular workplace was much more likely to succeed than the one referred to ‘social activities’ and sheltered employment. Of course, the latter was likely to face steeper barriers to employment (and that’s why she was referred to those programs). However, the evaluation evidence strongly suggests that even in such cases a program is more likely to succeed if participants are placed as early as possible to a regular work environment where they are treated (as far as possible) as a regular paid employee. This was the experience, for example with Individual Placement and Support (IPS) services for people with severe mental illness in Australia which are also being trialled in Norway.

On the other hand, programs that emphasise social support or work outside mainstream employment, and neglect the employment objective, such as the ‘Special Municipal Projects’ in Denmark and Personal Support Program in Australia are relatively ineffective in improving job prospects due to their ‘lock-in effects’.

Conclusions and suggestions

The QP appears to have achieved what few programs assisting the most disadvantaged unemployed people do: a significant and sustained improvement in their job prospects (of more than 10 percentage points) over the long term. Norway deserves to be congratulated for investing in long term unemployed people when other countries that once were once pacesetters in employment assistance for that group (including Australia, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom) seem to have retreated from earlier commitments in pursuit of short term budget savings (by either failing to subsidise intensive assistance for people unemployed long term or sharply reducing labour market assistance spending across the board).

It remains to be seen whether the positive early results of the QP will hold as the program matures and is brought up to scale.

It’s important to target the program to those most likely to benefit, and understand which elements of the program contribute most to these outcomes, because the program is loosely targeted and relatively costly and it may not need all of its elements to sustain its outcomes as it is scaled up.

Targeting would be improved by using a statistical assessment tool such as Australia’s Job Seeker Classification Instrument, in addition to long term unemployment status. This would also facilitate evaluation.

Previous evaluation evidence suggests that low caseloads and intensive support with a strong and direct employment orientation make the greatest difference for this target group. It’s important that this element is maintained and upgraded.

The benefits of this intensive support would be maximised if the program had a consistently strong emphasis on employment in the regular labour market, rather than sheltered jobs or social support in its own right. Experience with similar programs suggests that this requires considerable investment in recruitment and support for prospective employers. Caseworkers need a combination of labour market knowledge and nous, and the skills and social awareness to deliver the social support component of the program.

On the other hand, employment incentives are probably less important for this target group than for less disadvantaged jobseekers. The program may be equally effective without a non-means tested benefit payment. For example, a 50% reduction in benefits for every Krone earned may still encourage people to take on part time jobs (and this is more liberal than most social assistance income tests).

Adequate and stable income support is nevertheless important – both to prevent poverty and support engagement with the program. If this is lacking in Norway’s social assistance system, maybe it’s time to give it a firm legislative basis as other countries have rather than leave vital matters such as rates of benefit to the discretion of each Municipality. If social assistance clients need financial encouragement and support to participate in programs like QP, consideration could also be given to a modest ‘program participation supplement’.

Finally, robust evaluation is essential: both to establish which elements of the program work best and in what combination; and to win the inevitable arguments over secure and permanent financing. Finance Ministries care about long term fiscal impacts so its worth evaluating them carefully and thoroughly (even though the social impacts are equally important). The road to effective activation of long term unemployed people is littered with too many small scale, temporary, pilot schemes. The QP is a rarity that’s worth preserving and improving.

Scarcity: The use and abuse of psychology to reduce unemployment.

The idea that psychology (rather than shortages of jobs or skills) plays a role in unemployment is controversial. Yet employment service providers report that motivation makes a difference. A decade ago, an Australian Government study argued that the attitudes of unemployed people influenced their job prospects. But it left many questions unanswered: what lay behind those attitudes? Where they permanent or a fleeting response to current circumstances? A new book by American economist and psychologist team Mullainathan and Shafir gives us new insights into how people respond to poverty. It reveals how ‘scarcity’ shapes people’s lives and behaviour. This has implications for the way governments treat unemployed people.

Along with employment opportunities, skills and financial incentives, the motivation of unemployed people to search for work has an impact on their employment prospects. This can be viewed in three different ways.

The ‘homo economicus’ view holds that this is due to financial incentives. If people don’t increase their incomes much by working then they might ‘rationally’ decide to remain on income support. Financial incentives are always important, but don’t seem to explain much of our 6% unemployment rate. Most unemployed people are single. A single unemployed adult would more than double their disposable income by taking a full time job at the minimum wage. The rate of unemployment in Denmark is similar yet unemployment insurance payments there are typically equal to 90% of a modest fulltime wage.

A second view is that people’s attitudes – shaped by their family and social environment – hold them back from improving their lives. This is the so-called ‘culture of poverty’ theory. Advocates of this view such as Laurence Mead , argue that labour market reform and better financial incentives won’t do much to reduce unemployment. Paternalistic polices (such as Australia’s ‘Work for the Dole’) are the answer. While obligations to search for jobs do reduce unemployment, evidence is lacking that most social security recipients suffer from the kind of social ‘dysfunction’ hypothesised by Mead.

A third view, based on new research informed by behavioral economics, holds that the experience of poverty and unemployment itself holds people back. In addition to a lack of access to jobs, skills and opportunities, people living in poverty experience scarcity, and scarcity messes with the mind.

(1) It’s about attitude

The view that people’s attitudes towards unemployment affect their job prospects was presented in a study commissioned by the Howard Government in 2001. This ‘attitudinal segmentation’ study commissioned by the Australian Employment Department classified unemployed people according to their attitudes towards unemployment as (among other categories) ‘drivers’, ‘cruisers’ or ‘withdrawn’:

“In 2001 the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR) commissioned a study to develop a model of job seeker attitudinal segmentation, in which job seekers were grouped based on their attitudes towards finding work. The model was developed in several stages. In-depth interviews with a range of job seekers were first undertaken to identify what underlies job seekers’ attitudes and drives their behaviour. This research resulted in the development of a framework of eight job seeker segments.

Job seekers were asked to agree or disagree with each of the attitudinal statements using a 10-point scale for their responses. Extensive statistical analysis of responses to the attitudinal statements was undertaken to develop an algorithm to allocate job seekers to segments, as well as to quantify the segments.” p3

The research used the same tools applied by market researchers to segment their potential customer base. The results of this research are summarised in the figure below:

How might such research be used? The Department argued that:

How might such research be used? The Department argued that:

“The characteristics associated with each of the segments can help identify the types of

assistance required to most effectively generate the desired behaviours of active job search, economic participation and reduction of income support reliance. The survey also identified that more than half (57%) of job seekers were in the less motivated segments. This indicates a strong focus for assistance on increasing the “benefits” of job search and paid employment and decreasing the “costs” of moving from unemployed to employed.” p20

There’s nothing novel about this prescription. It comes from the ‘homo-economicus’ textbook with its emphasis on work incentives. It’s a short step from here to punitive ‘solutions’. In a presentation in 2003 which referred to the attitudinal segmentation research as evidence for welfare ‘dependency’, Peter Saunders, then with the Centre for Independent Studies (CIS), cited Mead in support of time limits on unemployment payments:

“As Lawrence Mead puts it: “Disadvantaged people without jobs find no end to reasons why working is impossible for them… They avoid personal responsibility and blame circumstances beyond their control…a mentality is at work that refuses to believe that opportunity exists, even when it does” (Lawrence Mead, ‘The New Politics of Poverty’ Basic Books, New York, 1992, pp.143-5)” p13

The political reaction to this research was predictable. The then Employment Minister turned his attention on the 16% of job-seekers identified as ‘cruisers’, argued publicly that ‘cruising’ was the reason many failed to show up at compulsory interviews, and promised to ‘get tough’.

Missing from the ideological reactions to this research was any serious attempt to work out where these ‘attitudinal’ responses to unemployment came from. Were they due to a ‘mentality’ among poor people as Mead suggests, were people reacting to financial incentives (the payment of benefits), or was something else going on? Until we work his out, classifying unemployed people according to their ‘attitudes’ will only reinforce stereotypes.

There were plans to use the attitudinal ‘segments’ identified in surveys such as this one to inform the provision of employment services, but they came to little. The idea that the kind of assistance (or punishment) unemployed people receive should depend on their responses to a psychological survey carried serious risks for unemployed people and governments. ‘Orwellian’ is a word that springs to mind.

Some providers do use their own assessments of people’s psychological reactions to unemployment to inform service provision. One approach used in Australia takes account of the impact of fear and self esteem on motivation among job-seekers. Providers using this model place less immediate emphasis on active job search where they identify these factors as barriers to employment.

Other providers use their own assessment of people’s motivation as a signal of whether it it is worth investing in employment assistance. Since motivation is not measured by the assessment tool used by Centrelink to determine the financial rewards for providers if they find someone a job (and it would probably not be possible to measure it accurately), there are financial benefits for providers who can identify which of their most ‘disadvantaged’ job-seekers are more ‘motivated’ (and therefore more likely to find a job with a bit more support). The problem with this strategy is that people whose motivation is impaired by severe labour market disadvantage will be ‘parked’, that is denied help beyond the minimum contractual requirements. The most effective providers don’t ‘park’ people who seem to lack motivation right now. They make an effort to find out why, and work out a way to engage them by holding out the prospect of employment.

(2) It’s about how we respond to our circumstances

An alternative view is that poor people’s attitudes and responses to their circumstances are shaped by their experiences at the time rather than a fixed outlook on life (e.g. ‘ambitious’ or ‘lazy’), or economic incentives.

A new body of research in psychology and behavioural economics offers insights into the way people adapt to poverty. To my mind (as someone who has worked with unemployed people), these insights are more grounded in reality than either ‘homo-economicus’ or the view that unemployment and poverty are signs of deeper social dysfunction. This is not to say that economic incentives and social background are unimportant: in some cases they make all the difference. It’s just that they don’t provide a firm evidence base for policies to reduce poverty or unemployment in the majority of cases.

A new book by American economist and psychologist team Mullainathan and Shafir neatly summarises a raft of recent research on how people respond to ‘scarcity’ . As the authors point out, it’s not just a scarcity of money that affects behaviour. Scarcity of time can produce the same results.

“Scarcity captures the mind. When we experience scarcity of any kind we become absorbed by it. …For the hungry, that need is food. For the busy it might be a project that needs to be finalised. For the cash strapped it might be this months’s rent payment. ….Scarcity changes how we think.”

The authors note that this has a positive side: people experiencing poverty are often better at managing their weekly budget because their minds are focussed on financial survival. But there’s a downside:

“Because we are preoccupied by scarcity, we have less mind to give to the rest of life. We can directly measure mental capacity or, as we call it, ‘bandwidth’. We can measure fluid intelligence (a key resource that affects how we process information and make decisions). We can measure executive control, a key resource that affects how impulsively we behave. And we find that scarcity reduces all these components of bandwidth. Being poor reduces a person’s cognitive capacity more than going without one full night without sleep. It’s not that the poor have less bandwidth as individuals. Rather the experience of poverty reduces anyone’s bandwidth.”

The authors offer a few practical examples. Firefighters in the US are more likely to die from motor vehicle accidents than other people. In their rush to respond to a call, with their minds fully occupied with dozens of urgent tasks, they often forget small things like buckling their seat belts. Similarly, the greatest risk from mobile phone use while driving does not come from holding the phone: it’s the loss of attention to the road while we speak and listen.The authors call this ‘tunnelling’:

“The narrowing of the visual field in which objects inside the tunnel come into sharper focus while rendering us blind to everything peripheral, outside the tunnel.”

They illustrate this with psychological tests. Before undergoing a standard test of cognitive ability, people on different income levels were asked to imagine how they would deal with a situation where their car required a $3,000 in mechanical repairs. To those on higher incomes, this wasn’t too much of a distraction. It didn’t have much affect on their scores on the test. For those on low incomes it was too close to the bone. Their scores plummeted. The distraction of working through a financial problem had a similar impact on their test scores as the loss of a night of sleep.

At a practical level, ‘tunnelling’ means that people who are short of money are more likely to focus on their immediate needs than future plans. People in poverty are often too busy juggling their finances, and responding to the minor and major crises related to poverty (the threat of electricity disconnection or eviction, finding the money for a school excursion, or chronic ill health) to raise their horizons beyond short term survival.

Once again, we should careful not to fall back on stereotypes. Do all people in poverty fall into this trap of short-term thinking? Clearly not. But the psychological researched cited by Mullainathan and Shafir suggests that it is harder for people whose minds are focussed on immediate survival and crisis management to make plans to improve their circumstances over the longer term, including through effective job search.

How many unemployed people face these circumstances is an open question, but with Newstart Allowance set at $37 a day financial worries are rarely far from people’s minds. A recent Senate Inquiry into proposed changes to benefit waiting periods revealed that 70% of people who apply for Newstart Allowance seek a waiver of the standard one week waiting period on financial hardship grounds. Most enter unemployment with few resources behind them. For example, most people on Newstart Allowance rent their housing and about half don’t own a car.

Policy applications

The insights from ‘scarcity research’ have implications for the way we provide services for unemployed people, for example, the treatment of people when they first apply for unemployment payments.

Much of the recent debate over solutions to unemployment has focussed on how new claims for unemployment payments should be treated. This is often based on the simplistic view that ‘welfare creates its own dependency’, so that once people enter the system they will become stuck there.

In the 2014 Federal Budget, the government proposed that young unemployed people be made to wait for 6 months for payment in the hope that this would spur them to find a job. Like proposals to put a time limit on benefits, this is based on a ‘homo economicus’ view of unemployment: change incentives and people will respond. Yet few labour market economists think this is a good idea. It ignores the demand side the labour market (a lack of jobs) and leaves people exposed to poverty. This is the ‘starve them into submission’ approach to unemployment. The 2014 budget proposal (and the 1 month wait proposed in 2015 after the 6 month wait was rejected by the Senate) tried to reduce the risk of impoverishment by exempting people assessed as having a higher risk of long term unemployment, but such assessments are far from 100% accurate. If there aren’t jobs available where people live that are suited to their skill level, then even less ‘disadvantaged’ unemployed people will remain out of work. This harsh approach shifts the financial risk of unemployment from government to unemployed people.

Paternalists argue for a different approach: impose stringent requirements (such as intensive job search) backed by close supervision of unemployed people. The idea is that those who can easily find employment will leave benefits more quickly, while those facing greater difficulty can be identified and offered more help. The advantage of this approach over long waiting periods is that on the face of it income support is not denied to people and it at least makes a serious attempt to treat these two groups differently. And there is evidence to suggest that supervised job search helps reduce unemployment by keeping people engaged with the job market and improving the effectiveness of their efforts to find work.

It’s not so clear when and how employment requirements should be applied. One view holds that job search and other requirements (such as working for the dole) should be imposed intensively as soon as people claim benefits, in the hope that people with good job prospects don’t persist with their claim. This idea is called ‘diversion’.

When this strategy was applied to sole parents claiming Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) benefits in the United States as part of a welfare ‘reform’ in the mid 1990s, it did turn many people away from income support, but not just those who didn’t need it. Many financially disadvantaged people who had difficulty dealing with public bureaucracies or meeting work requirements (for example due to a disability) were ‘turned away’ from benefits and experienced severe hardship. A study by Acs found that successful claims for TANF declined sharply yet the financial need for income support did not. Blank found that a decade after the US welfare ‘reform’, one in five low-income mothers at risk of poverty received neither TANF nor wages for a year at a time. Most of this group had virtually no source of income and they and their children were impoverished.

In 2005, the Australian Government trialled an experiment called ‘rapid connect’ in which unemployed people claiming benefits were referred more quickly to their first Job Network (employment service) interview. Instead of being given 14 days to register with the Job Network, they were required to do so within two days of their first appointment at Centrelink. When this was evaluated it was found to increase the probability of employment within the first 14 days, though from a low base – from 1% of applicants to 4%. Unfortunately the evaluation did not examine what happened to people who did not pursue a claim, including the extent to which they reapplied later. ‘Rapid connect’ had a downside. Unemployed people had too little time and too little information to choose the Job Network provider best suited to their needs. The majority did not make a choice and were assigned to a service by Centrelink, or simply opted for the nearest provider. This meant that people were often poorly matched with providers. If they didn’t find employment quickly, this was likely to reduce their future job prospects.

It also meant that from the outset, their relationship with employment services was passive. People were following requirements rather than taking the most effective action to find a job.

‘Scarcity’ theorists would advocate a different approach. Rather than force people to undertake intensive activities (including making their first contact with unfamiliar services) in a rush when their minds are focussed on how they will pay their rent and feed themselves, assure them that financial support will be provided if they register with an employment service and give them the time and information they need to choose one.

The first interview with an employment service provider would also be structured differently. Instead of gathering information in a mechanical way (following screen prompts) to populate a standard list of activity requirements and pushing people to sign immediately, it would better to start with an open ended discussion of how they see their career goals and job prospects, so that the focus turns to their own plans to secure employment and how the provider can help. This shifts the responsibility and initiative to where it should lie, with the job-seeker. Benefit requirements should be explained, but that could come at the end of the interview, once a positive relationship has been established with the consultant. It would help if providers were paid to spend more than half an hour with people in the first interview.

Scarcity theory also offers insights into the reasons people miss appointments with Centrelink and employment services, and what might be done about this. For at least a decade, around one third of these interviews were missed. There are often good reasons for this, including that the person has found employment or that they are ill. Yet a small minority of job-seekers account for a high proportion of missed appointments.The main response of successive governments to this problem has been to tighten penalties for non attendance. Some of these changes were sensible – including the idea of suspending payments until the person attends an appointment, and then restoring them. Most people who still need income support quickly contact Centrelink and the appointment can be re-scheduled.

Less attention has been paid to the reasons people miss appointments. The Employment Department surveys unemployed people from time to time about their experience of employment services. Why not ask whether they missed appointments, why this happened, and what might be done to make it easier to meet their requirements? Innovations such as reminders by text message have made a difference, but more that could be done, especially for people who are likely to face the greatest difficulty such as those with limited literacy or poor mental health. Sanctions could then be limited to the minority of people who deliberately fail to comply.

When unemployed people are ‘tunnelling’ in response their immediate problems, we need to find better ways to bring their attention back to requirements such as employment service appointments. Simply threatening to cut payments may be counterproductive: some people will avoid contact out of fear. People sometimes avoid opening letters from Centrelink altogether for this reason.

Finally, there is something governments can do to reduce financial scarcity for people who are unemployed: improve the Newstart Allowance. Making people live and search for work on $37 a day doesn’t improve people’s job prospects; it degrades them.

Does Work for the Dole work?

The Australian Government is determined to expand its flagship Work for the Dole program. From July 2015, working for benefits for 15 hours a week will be the default activity for 6 months of every year for unemployed people on Newstart or Youth Allowance. One fifth of employment services spending is devoted to the program – around $300 million a year. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in remote communities face continuous Work for the Dole as long as they receive unemployment payments. The scheme has always been controversial, but does it work? This blog looks at recent evidence of the impact of ‘work for benefits’ schemes on transitions to paid employment in the UK.The answer: not much at all.

The birth, decline and re-birth of Work for the Dole

Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s first Ministerial gig in the Howard Coalition Government was in employment services. One of the first programs he expanded was Work for the Dole.

‘If they’re not working for wages they’ll be working for the Dole’ (Tony Abbott, Minister for Employment Services)

Work for the Dole was the Howard Government’s flagship employment program. By the mid 2000s, it was the default compulsory activity for long term unemployed people for 6 months of every year. ‘Job avoiders’ had to work for their benefits for 11 months a year.

The Rudd Labor Government kept Work for the Dole as one of a series of compulsory activities organised by Job Services Australia providers for long term unemployed people. Since it was no longer the ‘default’ activity for people who did not choose another program, and was no longer separately funded (instead JSA providers had budgets to draw upon to finance a range of options), participation in Work for the Dole diminished in favour of vocational training programs.

Now it’s back with a vengeance!

The program is being expanded across the country from July 2015. People on Newstart Allowance for 12 months will undertake 15 hours a week’s unpaid work for 6 months, unless they’ve already enrolled in an alternative employment or training program approved by their Jobactive (formerly Job Services Australia) provider. People under 30 years will work unpaid for 25 hours a week after 6 months’ unemployment.

In remote Indigenous communities, people on unemployment payments will face continuous ‘Work for the Dole’ for 25 hours a week. Unlike the previous Community Development Employment Program in which they worked in community-controlled services and received ‘top up’ payments (so that it was more like waged employment), they will have to work for benefits in community jobs and projects organised by Work for the Dole Coordinators contracted by the Government, many of whom are private for-profit companies.

Finding quality placements on such a large scale will be a challenge. The Government has even suggested that picking up and dropping off their children from school will count as participation in Work for the Dole in remote Indigenous communities.

Controversy

From its beginning in 1997 Work for the Dole attracted controversy. Some argued that unemployed workers were being exploited in work for which they were paid less than the hourly minimum wage. While 15 hours a week of work for benefits was close to the minimum hourly wage at that time, the ‘full time’ variant of Work for the Dole introduced later required 25 hour’s work each week (about $10 per hour in current values). Others criticised the nature of the work on offer (usually ‘make work’ activity in low-productivity jobs) and the lack of vocational training.

Supporters argued the program improved work motivation and ‘soft skills’ like punctuality and communication and improved self esteem, though an early official evaluation of its impact on self esteem, by Dr Winefield found that it had no impact and that participants were already strongly motivated to work:

“Although, WFD had no impact on participants’ self-esteem, it had clear ongoing benefits on other measures of psychological well-being, although whether these benefits were lasting or short-lived remains to be seen. Research has shown that self-esteem is sensitive to changes in employment status. The current finding implies that participants did not perceive WFD as a change in their employment status.

Similarly, although WDF had no impact on work involvement, the level of work involvement was so high that there was little room for improvement.” (Winefield, A 1999, “Measuring the impact of the Work for the Dole pilot projects on work ethic and self esteem.”)

The views of participants varied: many objected to being forced to undertake work they felt wasn’t helping find paid work while others enjoyed the work or companionship with fellow workers.

Work for the Dole was not a labour market program. It did not have an explicit goal of helping people secure paid employment. Its official goals were mixed. They ranged from fulfilling a ‘moral’ requirement that unemployed people should ‘give something back’ for their benefits, to discouraging people from staying on benefits, to building soft skills and raising self esteem, and undertaking work of benefit to local communities. Depending on the audience and political mood, it was portrayed either as punishment for bludgers or a balm for the psychological damage of prolonged unemployment.

The program’s chameleon-like character made it hard to evaluate objectively. To my way of thinking, the litmus test for any employment program is whether it improves people’s job prospects. If not, then there’s no good reason to force people to undertake it. If it does stand a good chance of improving an unemployed person’s job prospects (if it’s relevant to their particular circumstances and there’s no ethical objection to the program itself) then it’s reasonable to require people to participate.

Although Work for the Dole was not formally a labour market program, the Howard Government nonetheless claimed that it improved people’s job prospects. Whether this was the case has been debated among experts from the outset.

Evaluating employment programs

The best way to assess this is a ‘net impact evaluation’, in which employment and off-benefit outcomes are compared over time with outcomes achieved by a similar ‘control group’ of unemployed people not referred to Work for the Dole. Employment programs have three different effects:

- Referral or ‘threat’ effects: Some people leave benefits rather than participate in the program

- Attachment or ‘lock-in’ effects: Participation in some programs reduces job search activity

- Program effects: Ideally, participation in a program improves employment prospects, for example by improving skills, putting people in contact with employers who might take them on, or by improving the efficiency of job search.

The overall impact of an employment program equals the referral effect + the program effect – attachment effects.

Quantitative studies should be supplemented by qualitative research that examines what actually happens to unemployed people and prospective employers when they participate in a program. Here I focus on net impact studies of work for benefits programs.

Previous studies of employment impacts

Economist Jeff Borland conducted the first and only independent net impact study of Work for the Dole. He found that participation in the original pilot scheme for young unemployed people in the late 1990s actually reduced the probability that unemployed people had left income support 12 months after referral to the program. He suggested this was due to attachment effects (they were too busy with Work for the Dole to search for jobs effectively). There appeared to be no significant program effects.

Subsequent official net impact studies found reductions in reliance on unemployment payments after referral to Work for the Dole. A study in the mid 2000s found that referral to the program reduced reliance on income support 12 months later by 6.1 percentage points. (Dept of Education Employment and Workplace Relations 2010, ‘Labour market assistance, a net impact study.’) That’s not a bad outcome for a labour market program but I’d be more confident of the results if they were backed by independent studies.

International studies of the effects of work for benefits schemes give little cause for optimism. An early literature review by MDRC Research, a prominent independent employment program evaluator in the US, found that work for benefits schemes did not improve people’s job prospects. A later report by the New Zealand Department of Labour concluded that neither New Zealand’s ‘community program’ nor similar programs in other countries improved job prospects.

Evaluating Work for benefits schemes in the UK

The best recent evaluations of work for benefit schemes were undertaken in the UK: a country with a rare record of careful independent evaluation of its labour market programs.

Here we examine recent evaluations of two UK work for benefit programs: the Mandatory Work Activity (MWA) program introduced in 2011 and the Community Activity Program (CAP) introduced in 2013.

Mandatory Work Activity

Mandatory Work Activity comprised 4 weeks of compulsory work for benefits for 30 hours a week. It was targeted towards people at risk of long term unemployment. It attracted much controversy and a successful British High Court challenge by an unemployed woman required to work for her benefit for a private employer.

The official evaluation of MWA found significant referral or ‘threat’ effects on the likelihood of benefit receipt:

“in the first 3 months MWA decreased the likelihood of claiming benefit by up to 5 percentage points: the proportion of referrals in receipt of benefit was 77% at week 10 compared to 82% for non-referrals at week 10. This strongly suggests that MWA had caused a deterrent effect of claiming benefit – a very high proportion (64%) of those who did not start signed off their JSA claim.

But, as shown in the graph below, these effects were reversed within another three months, as many of those who left benefits returned:

“However, in the subsequent period the impact decreased, returning to zero by

21 weeks following the referral (benefit receipt for both referrals and nonreferrals

was 74%). This means that in this period a higher proportion of

individuals returned to benefit amongst referrals than non-referrals. Overall,

the benefit impact during the first 21 weeks equated to referrals being off

benefit for an average of about 4 days more than had they not been referred.” p39.Effects of Mandatory Work Activity on benefit reliance

Note: green line represents MWA participants

Note: green line represents MWA participants

Crucially, the program had no impact on people’s employment prospects (so those who left benefits weren’t for the most part getting jobs and some were diverted to disability pensions). This is shown in the graph below:

“unlike for benefit, a MWA referral had no impact on the likelihood of being employed

compared to non-referrals. This suggests that although the benefit impacts suggested a deterrent effect from claiming benefit for the first 10 weeks, individuals were not going into employment.” p40Effects of Mandatory Work Activity on employment

Note: green line represents MWA participants

These data suggest that this short work for benefits program had significant ‘threat’ effects that were later reversed, but no impact on the future job prospects of unemployed people.

What did the Government do when it received this evaluation? It expanded the program! As labour market researcher Jonathan Portes pointed out in a blog:

“Briefly, what the analysis shows is that the programme as currently structured is not working. It has no impact on employment; it leads to a small and transitory reduction in benefit receipt; and worst of all, it may even lead to those on the programme moving from Jobseekers’ Allowance to Employment and Support Allowance. Sadly, the DWP’s press release doesn’t mention any of these key points. Nevertheless, one would naturally assume that as a consequence the programme would be redesigned to achieve better outcomes. However, in a Written Statement, the Minister for Employment said:

‘I am also pleased to announce the Government has decided to expand the Mandatory Work Activity scheme. The expansion will enable Jobcentre Plus to make between 60,000 and 70,000 referrals to Mandatory Work Activity each year, based on the current experience of the scheme, at a cost of an additional £5 million per annum. This decision has been taken as the result of careful consideration of the positive impacts demonstrated within the Impact Assessment.’Unfortunately (says Portes) it is very difficult indeed to reconcile this statement with the impact assessment itself.”

Community Action Program

In 2013 a new work for benefits program called Community Action Program (CAP) was trialled for very long term unemployed people (2 years out of work). This was carefully evaluated as part of a ‘very long term unemployed trailblazer’ scheme.

“The scheme had these features:

A randomised controlled trial to give a high degree of confidence that any observed differences in outcomes are attributable to the support options,

- A 13 week pre treatment period to test deterrence, informing and maintaining awareness of forthcoming support throughout the period, and

- A 26 week period of treatment consisting of either:

– Standard Jobcentre Plus support – this is the control group within the trailblazer and consists of flexible and personalised adviser based support.

- Community Action Programme (CAP) – delivered by contracted providers and comprising 26 weeks of full time work experience or provider-led job search support.

Ongoing Case Management (OCM) – an intensive offer of flexible and personalised adviser based support, delivered by Jobcentre Plus (JCP) through increased interventions over 26 weeks.” p15

A randomised trial is the ‘gold standard’ of net impact studies. Unemployed people were randomly assigned to a treatment group referred to the CAP, an alternative scheme called ‘ongoing case management’ (an intensive form of job search assistance), or a control group who received ‘standard JobCentre Plus support’ (mainly job search assistance) as shown in this flow chart:

The likelihood that unemployed people involved in the trial were still receiving income support up to 91 weeks after referral to each of these three options was compared. The results are shown in the graph below: 68% of benefit recipients in ‘standard JobCentre Plus support’ still received benefits 91 weeks later, compared with 66% of those referred to CAP and 64% referred to ‘case management’. So referral to CAP reduced benefit reliance by 2%, which was 2% less than the impact of case management.

Effects of CAP, Case Management and standard job search assistance on benefit reliance

The graph below compares employment outcomes for those referred to CAP and the other two options in the trailblazer. It turns out that CAP had no significantly greater impact on employment than the standard ‘Jobcentre Plus’ option. Ongoing case management did increase the likelihood of employment compared with the standard service, by just 1%.

To summarise: six months of compulsory work for benefits had no significant impact on the future job prospects of very long term unemployed people and increased the likelihood of leaving benefits by just 2% compared with standard job search assistance (similar to that received by unemployed people assisted by Job Services Australia). More intensive job search help had better outcomes than work for benefits, even though work for benefits was a more expensive program.

Like Australian Governments, UK Governments just don’t seem to learn when it comes to work for benefit schemes – or don’t want to learn.

A fair summary of the pros and cons of these programs was offered by Tony Wilson from CESI, the British employment services advocacy body. His conclusion: it’s reasonable for unemployed people to be required to join programs that help them secure a job and Governments should fund them, but work for benefit schemes generally aren’t worth the effort.

Long term unemployment: what can be done about it?

The following is a paper I presented at the long-term unemployment conference in 2014. It argues that the fact that two thirds of people on Newstart Allowances have received it for over a year and half for over two years signals policy failure. Governments have failed to invest in the regular work experience, training and capacity-building, and connections with employers needed by most people who have been out of paid work a long time.