The emerging narrative on tax reform in Australia goes like this:

- Yes, the GST is regressive (as clearly shown by a recent ACOSS analysis)

- But we rely more than most of our ‘competitors’ on income taxes

- And this is harmful to incentives to work, save and invest

- So, we should ‘change the tax mix’ by raising the GST in order to reduce personal income or company tax rates.

This blog answers the question: which are more economically efficient – personal income taxes or consumption taxes?

Income and consumption taxes: what’s the difference?

To begin with, we need to clarify the difference between income and consumption taxes. We are all familiar with the personal income tax on wages, but income taxes also apply to investment income (capital gains, interest, rent and dividends) and to companies and other entities as well as individuals. An income tax taxes increases in an individual’s spending power from year to year, whether this comes from wages or an increase in the value of their investment assets such as property or shares.

On the consumption tax side, we are all familiar with sales taxes such as the GST. Many other ‘indirect’ taxes (such as Stamp Duties) also fall on mainly consumption as businesses and investors pass their cost on to consumers.

There are three key differences between our personal income tax and the GST.

First, personal income taxes are levied directly on taxpayers while consumption taxes levied indirectly through producers and retailers.

Second, a direct tax personal income tax can be, and is, levied at progressive rates (marginal tax rates that rise with income) whereas a consumption tax is generally levied at a flat rate (10% in the case of the GST). Exemptions for essential goods such as fresh food add an element of progressivity to the GST, but progressivity is much more difficult to achieve in an indirect tax.

The third difference is the most important one: income taxes tax that part of income which is saved and invested, whereas consumption taxes do not. This follows from the identity: income = consumption + saving.

So the key difference between an income and a consumption (or expenditure) tax is whether the portion of income we save is taxed each year. An income tax does this, a consumption tax does not.

While people are accumulating wealth, a consumption or expenditure tax is equivalent to a tax on wages since it falls on labour income but not investment income. On the other hand once people begin drawing down their wealth to spend it (mainly after retirement) they would be taxed on the draw-down of their capital, much as superannuation benefits were taxed up until 2007. So increases in wealth would still be taxed, but a later point in time. An income tax taxes annual investment returns from wealth whereas a consumption tax ‘waits’ until wealth is drawn down or spent.

More detailed analysis of the impacts of income and consumption taxes on equity and economic growth is offered by Brooks, Auerbach, and Henry.

Do we rely more on income taxes than other countries?

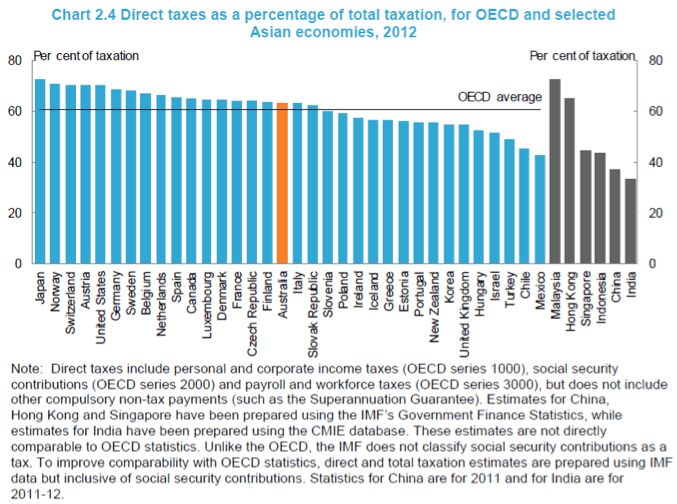

There is much public and media discussion about Australia’s tax ‘mix’ (the extent to which we rely on different taxes such as income and consumption for overall public revenue). Some argue that Australia relies much more heavily on income taxes than most OECD countries. When reliance on personal and corporate income tax is compared across the OECD in the Government’s Tax Discussion Paper, Australia appears to be an outlier (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Share of income taxes in all tax revenue

Source: Australian Government (2015), Tax discussion paper.

This comparison is misleading because most OECD countries rely heavily on social insurance taxes (these and not consumption taxes are the fastest growing taxes in the OECD). Social insurance taxes are a substitute for our taxes on personal income and payrolls. When social insurance and payroll taxes are included in the comparison, the Tax Discussion Paper shows that our overall mix between direct and indirect taxes is close to the OECD average (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Share of direct taxes in public revenues in OECD countries

Source: Australian Government (2015), ‘Tax discussion paper.’

Which is more efficient?

Since the 1980s, when most Governments struggled with low economic growth, high inflation and high unemployment, the debate over the ideal mix of tax between income and consumption has shifted from equity concerns to the impact of taxes on the economic efficiency and growth. Taxes have an economic cost, though of course this should be weighed up against the economic and social benefits the programs they finance.

A common tax reform narrative in Australia today holds that a change in the “tax mix” (which is code for a shift from taxing income to consumption) would greatly improve economic growth by strengthening work and saving incentives. According to this narrative, there is a trade off between the superior ‘equity’ of income taxes and the superior ‘efficiency’ of taxes on consumption.

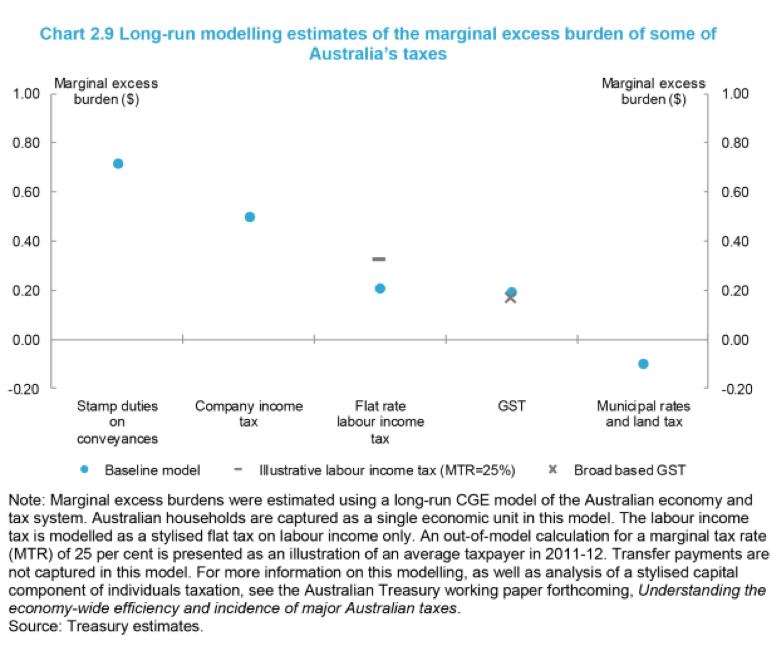

Treasury modelling of the economic impact of different taxes tucked away on page 32 of the Government’s Tax Discussion Paper provides the latest estimates of the ‘marginal excess burden’ of different Australian taxes.[1] Treasury separately released the details of that modelling.[2] The marginal excess burden (MEB) is the loss of future spending power across the economy per dollar of revenue raised from a tax. A low MEB means a tax is efficient; a high one suggests we might look elsewhere for public revenue.

Figure 3 is the graph from Tax Discussion Paper which summarises the results. Consistent with other studies, it finds that taxes on land have the least adverse effects on the economy (in fact they are growth enhancing), and that Stamp Duties and company income tax are among the least efficient (with marginal excess burdens of around 70 cents and 50 cents per dollar raised, respectively). The GST (19 cents) and a flat-rate income taxes on labour (21 cents) sit in the middle. The striking finding is that there is little difference in the economic efficiency of the GST and a flat rate labour income tax. Any difference probably falls within the model’s margin of error. [A progressive income tax is slightly less efficient according to Treasury’s model – that’s another story we’ll deal with later]

The other “eye opener” in Figure 3 is the difference in the economic impact of the current GST (which taxes about half of all consumption, represented by a dot in the graph) and a broad based one (which taxes all consumption, represented by an x). Again, there’s little in it, a difference of just 2%. It might be tough for retailers to distinguish between the GST treatment of a pizza and a pizza roll, but it makes little difference to the wider economy.

Figure 3: The relative economic efficiency of different Australian taxes

Source: Australian Government (2015), ‘Tax discussion paper.’

It is extraordinary that, despite thousands of column-centimetres devoted to the economic benefits of increasing the GST and cutting income tax in the media, this striking finding of recent Treasury research published in the Government’s Tax Discussion Paper has barely rated a mention.

To better understand the impact of income and consumption taxes on economic growth and efficiency, we need to unpack the way these taxes affect incentives to work, save and invest.

(1) Work incentives

The Treasury researchers argue that in the long run the GST and a flat rate labour income tax have equivalent impacts on labour supply incentives:

“Our estimate of the marginal excess burden on individual’s labour income and GST are very similar at around 21 cents and 19 cents respectively. This aligns with the intuition that taxation of labour income and GST both effect the real purchasing power of wages, with a similar incidence on labour supply.”

and:

“Compared to taxes with a relatively significant impact on economic growth and living standards (such as company tax), individuals income tax is usually considered to have a comparatively moderate impact on the behaviour of most people, and relatively minor adverse impacts on economic growth and living standards”, Cao L et al (2015), op cit, p41.

The intuition here is straight forward: both labour income taxes and consumption taxes reduce work incentives because they reduce the spending power of wages. As discussed, they both essentially fall on labour incomes, and drive a wedge between a worker’s wage and their spending power – but do so in different ways. A personal income tax reduces the after-tax wage whereas a consumption tax raises the prices of goods and services that can be purchased with a given wage. The claim that a switch to taxing consumption would improve work incentives would only be true if workers failed to notice that the purchasing power of their wages has declined.

This view is uncontroversial in the academic literature on taxation, except for one key difference between a direct personal income tax and indirect taxes on consumption: a direct income tax is targeted towards individual incomes while an indirect consumption tax falls mainly on household incomes. We return to that issue later.

There are grounds for concluding that a revenue-neutral switch from taxing income to consumption would reduce overall labour supply. A revenue-neutral switch to taxing consumption would require a higher average tax rate. The reason for this is that since the expenditure tax base excludes income from investment, it is narrower than the income tax base. The decline in growth of GST revenues since 2006, when household saving rose, illustrates this point. Therefore, a revenue neutral switch from taxing income to consumption would require higher overall taxes on labour, potentially reducing overall work incentives.[1]

Treasury’s modelling suggests that a progressive income tax (in which tax rates rise with income, represented by a dash in Figure 11) would have a more adverse impact on labour supply than a flat income tax (in which tax is levied at the same rate on everyone, represented by a dot). The marginal excess burden for a progressive income tax with a marginal rate of 25% is estimated to be 32 cents per dollar collected, compared with 21 cents for a flat income tax. This outcome is driven by an assumption in the model that as marginal income tax rates rise, they have a progressively greater (negative) impact on workforce participation.[2]

This assumption is debatable. In Treasury’s model (along with many others used to estimate the economic efficiency of taxes) households are represented by a single family. These models are unable to distinguish between work incentives for men and women, two income families and single income families, and families with and without children. Nor does they take into account the combined impact of income tax rates and social security income tests, which mainly impact on unemployed people and women in low and middle income families. These weaknesses are acknowledged by the Treasury:

‘Personal income tax is modelled as a flat rate equal to the effective average tax rate on household income. This simplification is a by-product of the design of the CGE model, which includes a single representative household. A major limitation with the modelling is that it does not capture the progressive individuals’ income tax scales in Australia, which is expected to have implications for the efficiency of personal income taxation. The transfer system and the impacts of the withdrawal of payments on effective marginal tax rates is also beyond the scope of this paper, but is nevertheless important in broader discussions about the economic effect of different taxes. Cao L et al (2015), op cit, p6.

and:

empirical research has shown that labour supply elasticities do significantly vary across the population, particularly between men and women (see Table 1 sourced from Dandie and Mercante, 2007). Thus the marginal excess burden for a tax rate of 25 per cent is presented as an illustration only.

As a summary of the literature on labour supply incentives also published by Treasury points out, in the real world it is low-income women not high-income men who are most sensitive to taxes when they decide whether to increase their paid working hours:

“The groups most likely to respond to high effective tax rates include the unemployed and lower-income earners (who often work part-time). Primary care givers, such as parents with young children, are also relatively responsive to effective tax rates but they also respond to other costs associated with working, such as child care.” Cao L et al (2015), op cit, p45

and:

“In the absence of any changes to payments or assistance, and all else being equal, targeting tax cuts at the lower end of the income spectrum should generate a higher participation response than if the same value of tax cuts were delivered at higher incomes, “p45.

So it’s not a foregone conclusion that a flatter income tax scale – which would increase tax rates for lower income earners and lower them for higher income-earners – would improve overall work incentives.

Unlike most research on the economic impact of taxes, Apps and Rees take account of the different labour supply responses of men and women, including women in single income and dual income families.[3] Their research emphasises the importance of the unpaid (caring) work of women as a substitute for paid work. One implication is that women, especially mothers whose potential earnings are modest, are relatively sensitive to the impact of taxes on the spending power of their wages. They find that a flatter tax scale is likely to reduce overall workforce participation, and also household saving since single-income families save less than dual-income families. They also find that a shift from taxing income to consumption would reduce labour supply because a consumption tax falls on household income rather than individual income (to the extent that households share their expenses), resulting in higher effective tax rates on “second” income earners who are mainly women with children.

In a shift from taxing income to consumption, work incentives could be further weakened by compensation arrangements. These typically rely on increases in social security and family payments which are income tested according to family incomes. These income tests are more likely to discourage women with children from re-joining the paid workforce (especially in low-paid jobs).[4]

(2) Saving incentives

In theory, moving from taxing income to consumption should encourage saving and investment but discourage workforce participation. As discussed, the cost of an income tax is shared between wage earners and investors whereas a consumption tax that raises the same revenue would exempt investment income from taxation and thus fall more heavily on wage earners.

When Randolph and Rogers from the Congressional Budget Office evaluated the economic effects of proposals to (completely) replace the US federal income tax with a flat rate tax on consumption in 1995, they concluded that the proposed reforms would probably modestly boost long-run economic growth but there was a great deal of uncertainty about the extent of any improvement, and a significant chance that they would reduce growth.[5] A key reason for this ambiguity was the offsetting impacts of higher saving and investment and lower workforce participation:

‘A comprehensive income tax reduces the rate of return to savings and the return ‘to working. If either saving or labor-supply changes, the income tax can result In lost welfare. In contrast, a broad-based consumption tax is equivalent in the long run to a tax on wage income alone. To raise the same amount of revenue as the income tax, tax rates on the narrower wage income base must be higher than they would be under the comprehensive income tax, and the tax rate on Income from saving would be zero. If saving is very responsive and labor supply is not, the consumption tax will tend to be more economically efficient than the income tax. The economic efficiency comparison depends critically, though not exclusively, on the size of the saving and labor-supply responses.’ Randolph & Rogers (1995), op cit p429.

Empirical evidence in support of the proposition that lower taxes on saving would raise aggregate saving levels is weak. Academic studies over the past two decades have examined whether “expenditure tax treatment” of saving (either by allowing full deductions for contributions to savings accounts or exempting investment income from tax) increases household saving. Engen, Gale and Scholz’s findings that tax breaks for saving influence the choice of savings vehicle (for example towards superannuation and away from interest bearing deposits) but are unlikely to boost household saving overall are consistent with much of this literature.[6]

A recent survey of the academic literature by the OECD concludes that tax breaks for saving that mainly accrue to high income earners are generally ineffective because they are likely to save in the absence of incentives.[7]

According to a more recent summary of the economic impact of taxes published by the OECD:

‘consumption taxation is often seen as favouring private savings relative to income taxation. However, the empirical evidence on the sensitivity of private savings to after tax interest rate changes is inconclusive: some studies found sizeable effects of interest rates on savings while other studies found no effects at all.’

And:

‘it is highly likely that the favourable tax treatment of pension savings only distorts the composition of savings without increasing the overall level of savings at the expense of tax revenues.’

(Johansson A et al (2008), ‘Tax and economic growth’, OECD Economics Dept. Working Paper 620.Paris. pp18, 31)

One potential economic efficiency gain from taxing consumption rather than income comes from an unexpected source: an increase in the taxation of the wealth of retirees as it is drawn down and spent. An income tax does not tax savings unless they are invested and yield an income stream. An expenditure tax taxes the draw-down of savings, which mostly occurs after retirement. For example, the GST reduces the spending power of retirement savings, and ‘expenditure tax treatment’ of saving for retirement calls for taxation of superannuation benefits.

A shift from taxing income to consumption is equivalent to a one-off lump sum tax on the savings of retired people. This is unlikely to affect saving and investment decisions and future economic growth because it is largely unanticipated and retirement savings are the product of decisions made throughout working life (sunk capital). To the extent that this windfall public revenue gain is used to reduce other taxes that distort economic decisions, it may improve economic efficiency.

Yet a large and sudden loss of spending power is unlikely to be popular among retirees and Governments would understandably face pressure to compensate them. The impact of compensation for low income earners and retirees adds to the uncertainty surrounding the impact of a shift towards taxing consumption on economic growth. Altig and colleagues found that compensation, especially of retirees for the reduced value of the savings, would substantially reduce any long run economic efficiency gain from taxing consumption more and income less.[8] More broadly, the larger the ‘compensation package’ for higher consumption taxes, the weaker the long term improvement in growth.

(3) Investment incentives

Another potential economic efficiency gain from taxing consumption rather than income comes from the removal of taxes on investment income, especially for investments across international borders. Investment is more ‘mobile’ than labour.[1] For example, people can more readily move their savings out of Australia than pull up stumps and work overseas. This suggests that taxes on investment income would ideally be lower that taxes on wages since investment is more responsive to tax levels. The risks to public revenue and economic growth from increasing mobility of capital (due to internationalisation and new technology) were emphasised by the “Henry Report”. [2]

Another way to reduce income taxes on investment without shifting from personal income tax towards a higher GST is to reduce income taxes on investment income relative to those on wages. ‘Dual income tax’ systems that do this explicitly can also be justified on the grounds that annual returns from investment are eroded by inflation.[3] Even without a formal ‘dual income tax’ most OECD countries, including Australia, do this already. The two largest sources of investment income – capital gains on owner occupied housing and superannuation – are taxed at well below standard marginal income tax rates. In addition, personal capital gains from other investments are taxed at half the standard rate. The Henry Report advocated maintenance of a differential between tax rates on labour earnings and investment income, with more consistent ‘discounted’ tax rates on different forms of investment income. We return to these proposals below.

To assess the impact of Australian taxes on investment levels, we need to distinguish between domestic and international investors, and between personal income and company income taxes. The main difference between personal and company income taxes is arguably that the latter falls on foreign investors only. This is due to the refunding of Australia’s company income tax to domestic investors through the dividend imputation system.

The Treasury research cited previously casts doubt on the view that lower income taxes on domestic investors would increase aggregate investment levels. It argues that, because capital is relatively mobile, global rates of return on investment matter more than domestic tax rates.[4] It might be added that a large part of domestic investment is in real estate, which is not a mobile factor.

On the other hand, the Treasury analysis finds that foreign investors are sensitive to our company income tax rates. This is the main reason that their estimate for the marginal excess burden for company income tax is 50%. They argue that in the long run company taxes fall largely on workers due to lower foreign investment in Australia, lower productivity, and hence lower wages.

This view is widely held in the academic literature, though it is contested. Treasury’s conclusion is based on two critical assumptions in their model: perfect capital mobility (without which Treasury says the marginal excess burden of company income tax could fall by 20%) and that ‘economic rents’ comprise about one seventh of profits taxed in Australia (if this is doubled then the marginal excess burden also falls by about 20%).

Economic rents are above-normal profits flowing from location-specific inputs (such as natural resources), or a monopoly position in a market (for example, financial services). A tax on economic rents has no adverse economic impact because it has no effect on investment decisions. It follows that the higher the share of economic rents in company profits, the less likely it is that a tax on such profits will have adverse impacts on the economy.

This was the logic of the Henry Report’s proposed trade-off between a mineral resources rent tax and a lower company income tax rate. In theory this would have shifted taxes from relatively mobile international capital to economic rents (in this case, those flowing from ownership of locationally-specific and finite mineral resources).[5]

Similarly, since land is immobile, a broad based tax on all private land (such as the council rates tax base) has virtually no adverse economic impact. Indeed, Treasury’s modelling estimates it would improve economic efficiency by 10%. This positive view of the economic effects of a broad based tax on land is widely held.

A further complication in any assessment of the impact of lower company income tax rates on economic efficiency is the use of company structures by personal investors and small business owners to avoid tax on their personal income. A lower company income tax rate represents a windfall gain to these taxpayers, to the extent that their individual marginal tax rate is higher than 30% and they are able to retain income in a private company for a number of years to take advantage of the differential. This narrowing of the personal income tax base is inefficient as well as inequitable since other taxpayers must pay more to compensate for resulting erosion of public revenues. These tax avoidance practices also distort decisions on how businesses and investments are structured and, since the tax preferred structures are more complex, raise the costs of investing and doing business.

A neglected aspect of the impact of taxes on economic growth is its effect on the efficiency, as distinct from the volume, of investment. Investment is not always economically beneficial and inefficient investment has an opportunity cost. The best example of this in Australia is over-investment by individual taxpayers in existing housing, which has achieved little more than an increase in home prices.[6] This is partly driven by the interaction of the 50% “discount” on taxes on individual capital gains and the uncapped deductions for investment expenses against income from wages which together encourage “negative gearing”.

As the Henry Report argued, Australian governments already tax most investment income at rates well below standard marginal tax rates on labour earnings, but we do so inconsistently and this distorts investment decisions away from opportunities that provide the best returns (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Effective tax rates on different investments held for 25 years

Source: Australian government (2015) ‘Tax discussion paper’, p60.

For this reason there are potential efficiency as well as equity gains from taxing investment incomes more consistently.[1] The ‘Henry Report’ proposed higher taxes on capital gains, lower deductions for “negatively geared” passive investments, and lower tax rates for income in the form of interest and housing rents. As the OECD notes:

‘differences in the personal income tax treatment of different forms of savings can be expected to distort the allocation of savings and reduce the growth potential of the economy. As most OECD countries do favour certain types of savings (such as owner-occupied housing, private pension funds) over others (such as bank deposits), there is scope to increase growth by reducing these distortions’. (Johansson A et al (2008), op cit, p28)

This points to an alternative strategy to improve the economic efficiency of the tax system to simply taxing income less and consumption more. Rather than reduce our overall reliance on taxes on income, improve the efficiency of the personal income tax system. Given that it raises around 70% of all Commonwealth tax revenue, and both investment income and labour income are taxed inconsistently, there is much scope to improve economic efficiency and equity at the same time by ‘broadening’ the income tax base (removing economically inefficient tax shelters) so that the same revenue can be raised with lower tax rates.

Modelling and myth

Tax reform modelling is an imprecise science. Advocates of a tax mix switch to consumption have quoted the findings of a 2008 OECD study which found that consumption taxes have less adverse impacts on economic growth than taxes on personal income.[2] This finding was based on a regression analysis of international data on long-term tax revenues and GDP growth rates. A close reading of this analysis reveals these important caveats:

‘Estimates of the effect on GDP per capita of changing the tax mix while keeping the overall tax-to-GDP ratio constant indicate that a shift of 1% of tax revenues from income taxes to consumption and property taxes would increase GDP per capita by between a quarter of a percentage point and one percentage point in the long run depending on the empirical specification. The magnitude of the estimated effect is larger than what would be reasonably expected. Given that there is a wide dispersion of the point estimates across specifications it is clear that the size of the effects cannot be measured precisely in a cross-country comparative setting. …Thus, the magnitude of the effects should be interpreted with caution.’ (Johansson A, et al (2008), op cit, p43)

The Treasury modelling discussed previously yields very different estimates of the marginal excess burden of the GST to a previous study commissioned from KPMG for the Henry Review. The KPMG estimate was 8 cents per dollar raised by a broad based GST compared with 17 cents in the Treasury model.[3] These differences apparently arise from different assumptions used in the modelling, and the updating of data.

This raises a serious question for policy makers: is our economic modelling of the impact of taxes reliable enough to draw firm conclusions for policy? This question was posed recently by a study commissioned by the “Mirrlees review” of taxation in the UK undertaken by the independent Institute for Fiscal Studies.[4] The authors concluded that arguments for the removal of taxes on investment incomes were getting well ahead of the reliability of the research.

Conclusion

The research on the long run economic impact of replacing income taxes with taxes on consumption can be summarised as follows.

The impact on economic growth of a switch from taxing personal income to consumption the long run may well be positive, but it is small and hard to quantify.

Any economic benefits are most likely to come from a windfall revenue gain from taxing the accumulated wealth of retired people as its is spent, which could be used to lower other taxes. These economic benefits would be reduced to the extent that they are compensated for this.

A switch towards consumption taxes is unlikely to improve work incentives, except to the extent that a flat tax is better for work incentives than a progressive one. But that’s contested: since consumption taxes are levied (for the most part) at the household level and at a flat rate, a switch towards these taxes could reduce overall labour supply by discouraging women caring for children from re-entering paid work.

In theory, shifting the tax base from personal income to consumption would improve saving incentives. In practice this and other savings incentives have little impact on overall household saving levels.

Investment is more likely to be boosted by a reduction in company income tax than by lower personal income tax rates since company income tax has a larger impact on foreign investment in Australia.[5] The impact would depend on the degree to which capital is mobile and company income taxes capture ‘economic rents’ (for example, from mining). To the extent that our company income tax does tax economic rents, it is an efficient tax. Any reduction in company income tax rates would have to be accompanied by measures to stem personal income tax avoidance through the use of private companies.

It is noteworthy that the main potential economic benefits from a tax mix change from income to consumption (a GST-company income tax trade-off and a one-off reduction in the value of the accumulated wealth of retired people) both pose major political challenges.

In short, the equity impacts of a change in the tax mix from personal income to consumption are quantifiable and negative, while any economic efficiency gains are uncertain and hard to quantify. Alternative tax reform options, such as broadening the income tax base by removing inefficient tax shelters, would improve equity and efficiency at the same time.

The longstanding argument over whether to tax consumption more and income less is unlikely to be resolved in the near future. By its very nature it opens up divisions in the community (between capital, labour and people out of paid work) that put the tax reform project, and any government that pursues it, at major political risk for minor economic gain.[6] Consumption taxes are an important part of the overall public revenue-raising effort but the case for relying more on them and less on income taxes has to be demonstrated, not simply claimed.

It’s time to move on from the old ‘tax mix’ arguments, and get to work on making both income and consumption taxes fairer and more efficient. Reform of inequitable and inefficient income tax shelters (including superannuation tax concessions, the combination of Capital Gains Tax concessions and negative gearing, and the use of private trusts and companies to avoid tax on personal income) would be a good start, along with the replacement of the most efficient State taxes (such as Stamp Duties) with more efficient ones (such as a broad based Land Tax).

[1] Australian Government (2015), ‘Tax Discussion Paper’.

[2] Cao L et al (2015), ’Understanding the economy wide efficiency and incidence of major Australian taxes.’ Treasury working paper 2015-1

1] Australia’s Future Tax System (2008), op cit.

[2] Johansson A et al (2008), op cit.

[3] That is, a GST with no exemptions.

[4] Banks & Diamond (2008), ‘The base for income taxation.’ Institute for Fiscal Studies, London.

[5] Our company tax ultimately falls on overseas investors rather than domestic ones, due to the operation of the dividend imputation system.

[6] A politically feasible change in the tax mix from income to consumption would be modest given the adverse distributional effects, and any economic benefit may well be offset by compensation arrangements.

[1] Freebairn J (2010), ‘Overview of Australia’s future tax system,’ in Evans C et al (2010), ‘Australia’s future tax system: the prospects after Henry’, Thomson Reuters, Sydney

[2] Australia’s future tax system (2008), Report to the Treasurer.

[3] Sorensen P (1993), ‘From the Global Income Tax to the Dual Income Tax: Recent Tax Reforms in The Nordic Countries.’ Economic Policy Research Unit, Copenhagen Business School.

[4] Cao et al (2015), op cit.

[5] Australia’s Future Tax System (2008) ‘Report to the Treasurer.’

[6] ACOSS (2015), ‘Fuel on the fire,’ Tax Talks 2.

[1] This possibility is discussed further in relation to research by Randolph and Rogers, below.

[2] Cao et al (2015), op cit.

[3] Apps P & Rees R (2013), ‘Raise top tax rates not the GST’, Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper No 684, ANU Canberra. See also Apps P (2015), ‘The central role of a well designed income tax in the modern economy.’ Paper for conference: ‘100 Years: Where next for the Income Tax?’, 27-28 April 2015 Tax and Transfer Policy Institute Crawford School of Public Policy ANUhttps://taxpolicy.crawford.anu.edu.au/files/uploads/taxstudies_crawford_anu_edu_au/2015-07/patricia_apps_final_paper_27-28_april_2015.pdf

[4] Apps P & Rees R (2013), op cit.

[5] Randolph & Rogers (1995), ‘The implications for tax policy of uncertainty about labor supply and saving responses.’ National Tax Journal Vol 48 No 3.

[6] Engen E at al (1996), ‘The illusory effects of saving incentives on saving.’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol 10 No 4.

[7] OECD (2007) ‘Encouraging-savings-through-tax-preferred-accounts.’ Tax Policy Paper No 15 http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/encouraging-savings-through-tax-preferred-accounts_9789264031364-en;jsessionid=60bggq4a3mgk.x-oecd-live-01

[8] Altig D et al (1999), ‘Simulating Fundamental Tax Reform in the United States.’ American Economic Review, 91(3): 574-595.